Yesterday marks the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the American occupation of Haiti, a brutal 19-year affair that was largely put into place to protect U.S. business interests. In all, 50,000 Haitians were killed during the occupation.

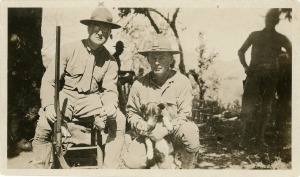

An American patrol in Haiti/photo-Wikimedia Commo

An American patrol in Haiti/photo-Wikimedia CommoSmedly Butler, a U.S. marine who served in Haiti and went on to lead the Marine Corps, famously described his role in Haiti as helping to prop up a “racket.” “I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in,” he wrote. “I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street.”

Today, the American occupation of Haiti barely exists in the consciousness of Americans. The fact that this chapter of Haitian/American history has no bearing on how Americans see Haiti today speaks volumes to the nature of our relationship with the country. To be clear, Americans feel sympathy for Haiti — Americans donated billions to earthquake relief, after all. Haiti is a place Americans generally feel bad for and want to help, but Americans feel that they don’t have much of a connection to Haiti.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Imperialism

Well before the New Deal and World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote Haiti’s constitution. In his position as assistant secretary of the Navy during the occupation of Haiti, Roosevelt proposed a new system of laws for Haiti that got rid of the Haitian prohibition on foreigners owning land in the country. This cleared the way for American sugar companies and other profiteers.

FDR embodies how imperialism is more than just a dark chapter in America’s otherwise triumphant history. I think it’s useful to think of imperialism the same way Ta-Nehisi Coates would have us think about racism. It’s not that America is a good country with a race problem. Racism is a fundamental part of American history. In this same way, you can’t separate out the history of the United States from the history of the United States’ imperialism.

It is common to gloss over America’s history of imperialism, and this has real world consequences today.

Marco Rubio and How to Help Haiti

A couple weeks ago, Marco Rubio held a hearing on the State Department’s role in Haiti. Rubio’s introductory statement included an illustrative sentence in which Rubio (or the staff member who wrote the statement) attempted to sum up the historical context for Haiti’s situation today. “Haiti has struggled to overcome its centuries-long legacy of authoritarianism, extreme poverty and under-development,” Rubio said.

In this way of see things, Americans think about Haiti as “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere” (another Rubio line from the hearing), and Haiti needs to overcome its “legacy” of its own problems. There is obviously no mention of the American occupation, the subsequent history of American meddling in Haiti or the previous history of France forcing Haiti to pay French banks backs for the “damages” of the 1804 revolution. Instead, Haiti is a country mired in its own “legacy” of deep problems.

As Rubio’s hearing progressed, Thomas Adams, the State Department official revealed another key aspect of how Americans think of Haiti. In describing how it is possible that the American Red Cross managed to waste hundreds of millions of dollars in its rebuilding efforts following the 2010 earthquake, Adams said, “it’s not easy to get anything done in Haiti.” In this commonly-held way of thinking about Haiti, Haiti is a quagmire. We’re doing what we can to help the place, and it’s a great victory if our charities or our government money succeeds in improving the country even marginally because Haiti is such an exceptionally messed up place. This feeds into what the seminal scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot termed “Haitian exceptionalism” — the idea that normal rules don’t apply to Haiti.

In this perspective on Haiti — so clearly articulated by Adams — not only is Haiti a charity case, but there are very low expectations for how much we can even help the country.

A Rights-Based Approach to Poverty

FDR in Haiti/photo-creative commons

FDR in Haiti/photo-creative commonsIf one considers the American occupation of Haiti and Haiti’s history more generally, there is another way of relating to Haiti. Instead of seeing Haiti as a separate entity, one could see the United States and Haiti as linked. If we think about a connection to Haiti, we are more likely to think about how Haitians have rights. We shouldn’t help Haitians only out of charity; we should do what we can to help Haiti because Haitians (and all humans for that matter) have rights. Especially if the United States is complicit in the history that took away these rights, we should work to make sure these rights are protected.

Adopting a rights-based approach has important practical implications. As the journalist Jonathan Katz points out, one of the biggest problems with aid today is that there is virtually no accountability in how organizations work abroad. Just as long as NGOs or development agencies don’t grossly mismanage funds, there are few consequences for failure. Approaching development as something people deserve would add a new seriousness to our relationship with places like Haiti.

Leave a comment